Soon after Fred and Adele started their regular classes with Alviene and after Fritz had returned to Omaha, one of the first things that Ann did was start looking for long-term accommodations more affordable than the Herald Square Hotel. The 1910 Alviene catalog lists advice on housing as one of the school’s services. “Accommodations can be arranged for in New York at moderate rates and in the immediate vicinity of the schools. A list of addresses of first-class furnished-room houses, boarding houses and hotels is kept on file at the office for the accommodation of students. Room and board $6.00 to $9.00 weekly. Furnished rooms $2.00 weekly and upwards. Table board $3.50 to $6.00 weekly” (The Alviene 16). Alviene suggested a boarding house on 23rd Street near the Grand Opera House. It had a furnished room on the second floor with a bed for Anna and cots for Adele and Fred. They shared a bathroom down the hall with other residents of the boarding house and took their meals downstairs (Riley 22). Classified advertisements from early 1905 in the New York World show nearly a dozen boarding houses on 23rd Street west of Seventh Avenue, with prices ranging from $1.50 a week for a “Nice, clean hall bedrooms, front” (235 W. 23rd) to $5 for a “large, pleasant front parlor, steam heat, bath” (313 W 23rd) (Advertisements 1905 January 16 & 23:6). The latter was in the building that had once been the mansion of Jim Fisk, whose Erie Railroad offices had been in the Grand Opera House.

The Astaires’ boarding house featured a bay window looking out over the noisy traffic of 23rd Street, where the screeching wheels and clanging bells of the cross-town trolleys that ran east from the 23rd Street Pier on the North River to the East River. When the Astaires arrived in 1905, 23rd Street was a busy neighborhood with a mix of stores, offices, theaters, and homes. The grand days when 23rd Street was the center of the rialto and the northern end of the “Ladies Mile” shopping district were waning, as large department stores, such as Macy’s, had moved to 34th Street at Herald Square, and theaters had begun springing up near 42nd Street and Times Square. But if there was bit of tarnish on the gilt of 23rd Street, it would still have been an excitingly diverse place for a young man from Omaha.

The first most distinctive sight on 23rd Street was the Flatiron Building, just three years old when the Astaires came to Manhattan. Its dramatic shape as well as its bright limestone and glazed white terra cotta façade with Beaux Arts ornamentation made it a magnet for sightseers. Its location across from Madison Square Park enabled artists to capture distinctive images of the building, which had been published across the country in magazines and guidebooks. Designed by Daniel H. Burnham and built in 1902 for the Chicago-based Fuller Construction Company, the building had become popularly known as the Flatiron Building because of its distinctive shape dictated by the triangular lot where Broadway and Fifth Avenue met at 23rd Street. It would be an area that became quite familiar to the Astaires in their first year in New York. In his autobiography, Fred mentions visiting the Flatiron Building as part of the sightseeing in their first few days in Manhattan (Astaire 16). Soon they would be living and studying on 23rd and would likely have walked by it several times each week.

With a junction of broad streets (Fifth Avenue and 23rd), the angled intersection of Broadway, and the expanse of Madison Square, winds from the north as well as the west or east would converge around the 22-story building and create an unpredictable wind tunnel, that became notorious for blowing off gentlemen’s hats and raising lady’s long skirts, so much so that one of the most popular tourist postcards of the era featured just such a scene. The phrase “23 Skidoo” seems to have originated during this time as well, either as a warning as to how one had to cross the busy street pushed by or straining against the wind, or as a warning by New York policemen to loafers hanging around the corner who hoped to catch a glimpse of wind-raised skirts.

A few steps away from the Flatiron Building was a brownstone at 14 West 23rd that had been the birthplace of Edith Wharton in 1862, but by 1905 the block between Fifth and Sixth Avenue had become home to major department stores: Stern’s at 38 West, Le Boutillier’s at 50 West, Bonwit & Teller’s (specializing in women’s clothing) at 58 West, Best & Company (specializing in children’s clothing) at 60 West, and McCreery & Co at 66 West, in the building that had originally housed Edwin Booth’s Theatre (Miller, Shakespeare Comes Home). In the middle of that block (54 West) was the city’s second location of Schrafft’s, and its first as a tea-room catering to shoppers at the neighboring stores. On the opposite side of the street were furniture, book and art stores, as well as the five-story Masonic Temple at the northeast corner of Sixth Avenue.

In the middle of the block at 55 W. 23rd was another big tourist draw, the Eden Musee. Originally opened in 1884, it was a cross between London’s famed Madame Tussaud’s with a wax museum, including a “Chamber of Horrors” in the basement, and a large music hall dubbed the “Winter Garden” seating 2,000 people, plus a gallery of stereopticons. The Eden Musee is credited as the first New York theater to show motion pictures as a permanent feature and was the first of Thomas Edison’s movie licensees (Miller, The Lost Eden Musee). In 1905, the admission rate was 50¢ (25¢ on Sundays) (“The Week in New York” 27).

The Sixth Avenue elevated railroad, which had been electrified in 1903, picked up passengers at the 23rd Station, making the corner a busy hub for workers, shoppers, and entertainment seekers. Between Sixth and Seventh Avenue, the 100 block of West 23rd featured Koster & Bial’s Concert Hall (101 West) and the parish house of Church of the Holy Communion at 130 West, which housed a branch of the New York Free Circulating Library. A year later it would relocate to 209 W. 23rd with Carnegie funds and be named for the Rev Dr. Muhlenburg, the first rector of the church. Across the street at 135 West was Proctor’s 23rd Street Music Hall. Painter John French Sloan lived at 165 West from 1904 to 1911 (23rd Street).

Between Seventh and Eighth avenues were a variety of residences, boarding houses, offices, restaurants, and institutions. At the southwest corner (200 West) was the School of Applied Design for Women, which offered instruction in making ornamental designs for carpets, wallpaper, furniture, and book covers. Established in 1892, it opened on 23rd Street in 1895, and in 1909 would move to 160 Lexington Avenue at 30th Street. Across the street at 215 West was the chief home of the Young Men’s Christian Association, which had moved to this location in 1904. Considered the finest YMCA building in the United States at the time, the eight-story building featured a roof garden, a cork running track, and a marble-lined swimming pool (About the McBurney YMCA - History).

Just a few doors away at 241-243 West was the Frank E. Campbell Burial and Cremation Company, the original home of what would later be known as the “Funeral Chapel” and then the “funeral home to the stars,” especially after the death of silent movie idol Rudolph Valentino in 1926, when thousands of people stormed the chapel. By that time Campbell had moved to Broadway and 66th Street and would later move to 1076 Madison Ave. at 81st Street. Campbell is credited with transforming the funeral business, moving the memorials from the homes of the deceased to funeral-parlor chapels and advertising heavily (Oppenheimer).

Perhaps the best-known location on the block still standing today was the Chelsea Hotel at 222 West. Originally opened in 1884 as a luxury apartment building, the 12-story building had become a hotel about the time the Astaires moved to 23rd Street (Baral 76). The original walls were three-feet thick to support the iron girders placed across them, making the hotel rooms nearly soundproof, which may have especially attracted the artists who had frequented the hotel, such as Mark Twain, Sarah Bernhardt, and Lillian Russell. The most famous restaurant on the block (if not the whole of 23rd Street) was Cavanagh’s at 258 West, which opened in 1876. Lillian Russell and her frequent escort, James “Diamond Jim” Brady, were regular patrons, especially when Russell was staying at the Chelsea Hotel just a few doors away. During elections, Cavanagh’s was patronized by Tammany Hall chiefs, and a large billboard for posting election returns was posted in the main dining room (Baral 98).

In the next block between Eighth and Ninth avenues, the Grand Opera House dominated the northwest corner. Just a few doors away at 313 West was the mansion of Jim Fisk. From 1882 to 1890, Lillie Langtry, “The Jersey Lily,” had lived at 361 West (Baral 100). In the 1905 New York City directory, the block seems to have been dominated by private residences or boarding houses.

Through the middle of Ninth Avenue ran the IRT elevated railroad and its 23rd Street station. The steam engines that rained soot and cinders down on pedestrians had been replaced by electric engines just two years before the Astaires arrived. The 400 block of 23rd Street between Ninth and Tenth avenues had been the home of Clement Clarke Moore, and his Chelsea Estate had been adopted as the name of the whole neighborhood. By 1905 this block was also primarily residential. Brownstones on the north side of the 300 block of West 23rd had been built in 1845 and were called the London Terrace. Demolished in 1929, they were replaced with apartment buildings also called the London Terrace.

In 1905, Tenth Avenue featured street-level railroad tracks for the New York Central freight line, dangerously crossing the busy 23rd street intersection. Just a few years after the arrival of the Astaires, the New York City Bureau of Municipal Research asserted that since 1852, the trains had killed 436 people. A city ordinance in the 1850s required a person on horseback to ride ahead of the train, making pedestrians and traffic aware of the train’s approach. Later known as the “West Side Cowboys,” they waved red flags and lanterns to warn those crossing “Death Avenue.” Decades later, the New York Central moved the rail above street level, and the new tracks just west of Tenth Avenue, opened in 1934, running through factories and warehouses to pick up goods (Berg). The last train ran along the elevated tracks in 1980, and they were abandoned until the creation of the High Line, which first opened in 2009.

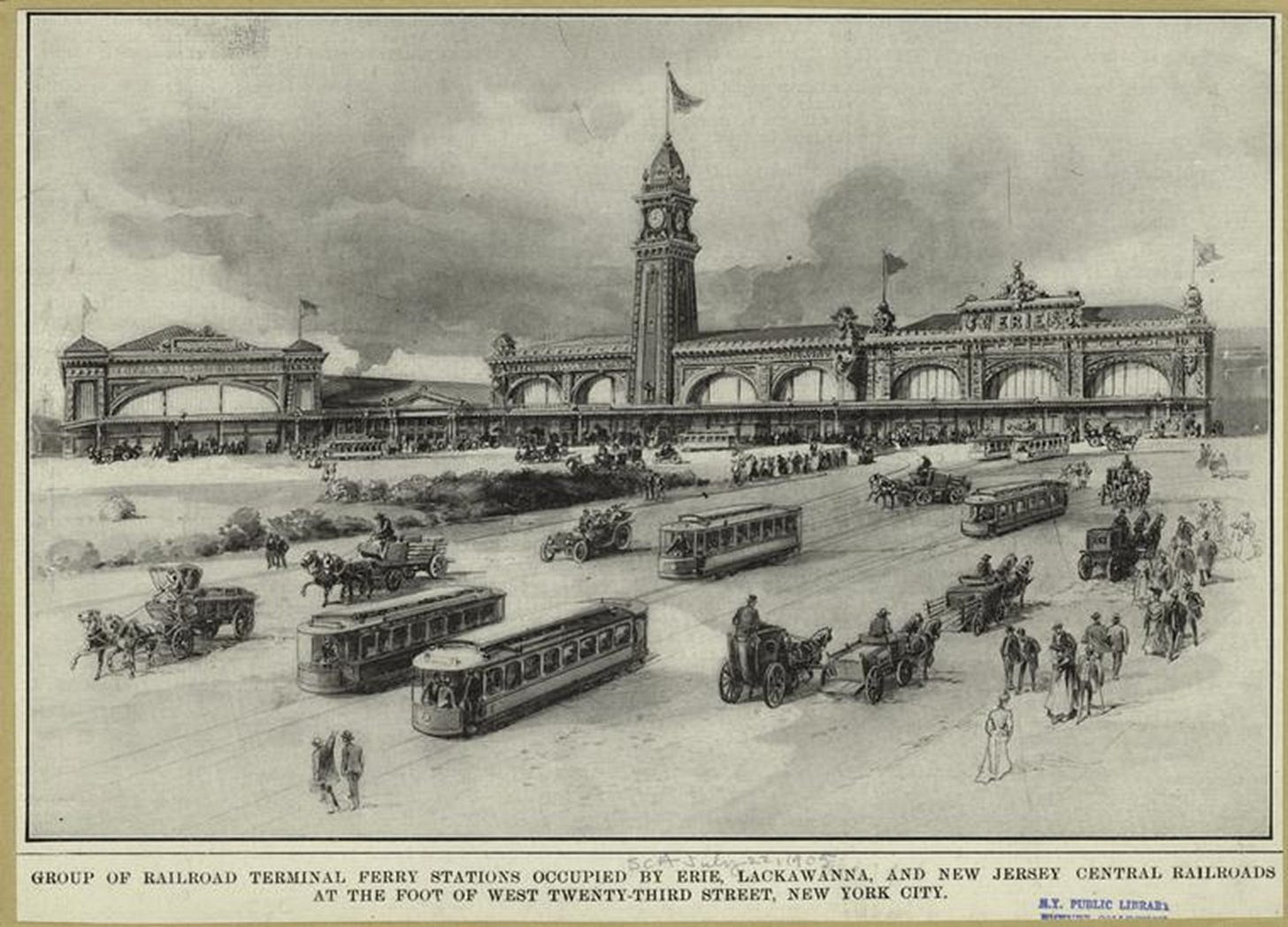

At the western end of 23rd Street were a group of railroad terminal ferry stations that had been transporting passengers across the Hudson River (or the North River as it was then more commonly termed) to Jersey City since 1868. The 23rd Street terminal complex included the Erie Ferry, which operated from 1868 to 1942 for the Erie Railroad. The Pennsylvania Ferry for the Pennsylvania Railroad operated from 1897 to 1910, when it was no longer necessary because of the opening of the North River tunnels and the Pennsylvania Station in 1910. The Jersey Central Ferry operated from 1905 to 1941, and the Lackawanna Ferry ran to Hoboken, New Jersey, from 1905 to 1947. Located just a few busy blocks from the boarding house where the Astaires were living in 1905, these ferry terminals would have been where Fred, Adele and Anna embarked on their first vaudeville tours later in the year and possibly where they met Fritz on his frequent visits from Omaha.

The three Astaires found themselves in the middle of this bustling street, whose primary impression for them must have been the haste and the noise, so very different from their life in Omaha. The same year that the Astaires arrived novelist Edgar Saltus described his impressions of the Flatiron District in a popular magazine:

… haste is in the air, In the effrontery of the impudent "step lively," in the hammers of the ceaseless skyscrapers ceaselessly going up, in the ambient neurosis, in the scudding motors, in the unending noise, the pervading scramble, the metallic roar of the city. Beyond is the slam-bang of the Sixth Avenue Elevated careering up-town and down, both ways at once. Parallelly is the Subway, rumbling relentlessly. Farther east are two additional slam-bangers. To the west is a fourth. Beneath them are great ocher brutes of cars, herds of them, stampeding violently with grinding grunts, and, on the microbish pavements, swarms such as Dante may indeed have seen, but not in paradise (Saltus 382-383).

SOURCES

"'23D, 235 W' Furnished Rooms to Let advertisement." New York World 23 January 1905: 6.

"'23D, 313 W' Furnished Rooms to Let classified advertisement." New York World 16 January 1905: 6.

About the McBurney YMCA - History <https://archives.lib.umn.edu/repositories/7/resources/6792>

Alviene, The. New York: The Alviene United Stage Training Schools, 1910.

Astaire, Fred. Steps in Time. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1959.

Baral, Robert. Turn West on 23rd: A Toast to New York's Old Chelsea. New York: Fleet Publishing, 1965.

Berg, Madeline. The History of "Death Avenue". 22 October 2015. 28 February 2019. <https://www.thehighline.org/blog/2015/10/22/the-history-of-death-avenue-2/>.

Miller, Tom. The Lost Eden Musee - "The Wonders of the World in Wax". 8 December 2010. 27 February 2019. <http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2010/12/lost-eden-musee-wonders-of-world-in-wax.html>.

—. Shakespeare Comes Home to 23rd and 6th. 28 June 2010. 27 February 2019. <http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2010/06/shakespeare-comes-home-to-23rd-and-6th.html>.

Oppenheimer, Jerry. Inside New York City's funeral home to the stars. 14 September 2014. 28 February 2019. <https://nypost.com/2014/09/14/inside-new-york-citys-funeral-home-to-the-stars/>.

Riley, Kathleen. "The Astaires: Fred & Adele." New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Saltus, Edgar. "New York from the Flatiron." Munsey's Magazine July 1905: 381-390.

"Week in New York, The." The Week in New York 5 March 1905: 27-29.