In January 1905, the Austerlitzes went the dozen blocks from the Herald Square Hotel to the northwest corner of 23rd and Eighth Avenue, entered the side door of the Grand Opera House, climbed dark, narrow stairs to the fourth floor, emerged into a large ballroom and met for the first time the man who would change their lives and their names: Claude Merzo Alviene.

Years later in his autobiography, Fred would add an extra “n” to Alviene’s last name, a mistake perpetuated by almost every biographer who relied on Steps in Time as the primary source for the Astaires’ early life. The major exception is Kathleen Riley in her 2012 biography The Astaires, who looked at original sources – mostly newspaper advertisements and the school’s own catalogs. Fritz Austerlitz had apparently seen an advertisement for Alviene’s school in The New York Clipper, a weekly entertainment trade newspaper to which he subscribed. Fritz might well have seen them in any number of show business periodicals, as Alviene had been advertising his school in a wide range of publications.

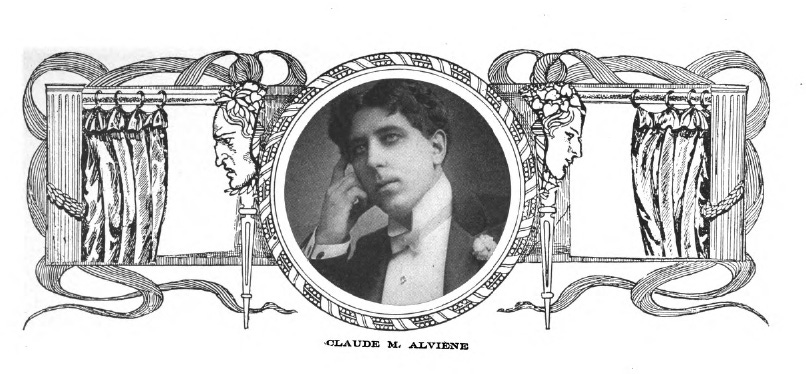

Biographical details for Alviene’s early life are inconsistent and foggy. He appears to have been born in New York City circa 1869 and died April 23, 1946. According to a profile published in The New York Sun (12 June 1910:II-9), Alviene’s mother and father started the Alviene School in the 1880s, but in several articles over the years he was purported either to have received dance training at La Scala (Marbourg 4) or even to have been the ballet master at Milan’s famed opera house (Schweitzer 907). According to a booking manager’s advertisement in the New York Clipper (12 March 1892:15), Alviene was the “greatest living sensational dancer on tiptoes with double skipping rope clearing real eggs 1½ inches apart.” That combination of extravagant claims and attention-grabbing routines would mark his choreography and his publicity for the next 40 years.

Alviene had been offering dancing instruction since the early 1890s, advertising waltz lessons in the New York World. Six months later he would be advertising $1 lessons in the New York Clipper for serpentine, Spanish, grotesque and character dances at the Alviene Conservatory at 154 Third Ave. near 15th Street (23 April 1892:14).

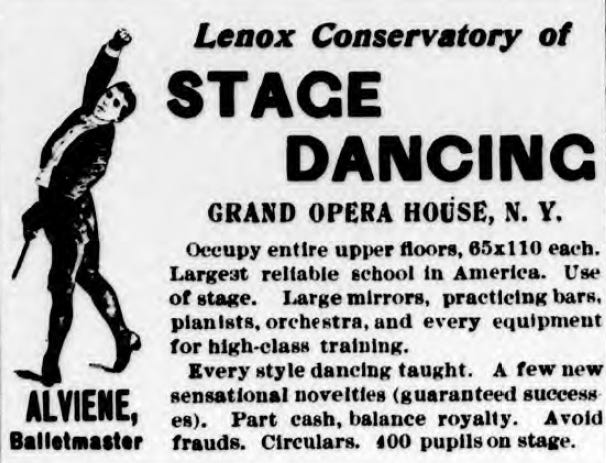

For the next five decades, Alviene would change the name and the location of his school multiple times, generally following in the wake of legitimate theaters moving uptown. Along with a Professor Sonati he would offer classes at 851 Seventh Ave., 431 Sixth St., and even in Brooklyn at 334 Broadway (New York World 26 April 1892:6). His Alviene Academy offered afternoon and evening classes at 613 Third Ave. near 40th Street (New York World 27 November 1892:38). By 1895 the school had been redubbed the Lenox Conservatory of Dancing and moved to a new location, the Grand Opera House, where he would stay for nearly 20 years. He briefly offered classes at a Harlem branch at 158-162 W. 125 St. (New York World 12 January 1897:6) and Metropolitan Hall at 127 Columbus Ave. (New York Journal and Advertiser 22 November 1897:13).

By the time the Austerlitzes arrived at the Grand Opera House, the conservatory had been renamed the Alviene School of Stage Arts with dramatic, stage dancing, and operatic departments. Ads described the school’s extensive facilities, including large mirrors, practicing bars, pianists, orchestra and “every equipment for high-class training.” In early 1907 the school was named the Alviene Institute of Dramatic Arts and had added an uptown branch in the American Theatre Building at 260 W. 42nd St., adjoining Hackett’s Theatre (New York Dramatic Mirror 5 January 1907:23). By 1910, still at the Grand Opera House, the expanded offerings led Alviene to rename his school the Alviene United Stage Training Schools (Theatre Magazine, August 1910:vi), and there were articles in entertainment weeklies that Alviene had signed a 10-year lease at the Grand Opera House and added 15,000 square feet of floor space, allowing them to occupy three floors with three large auditoriums, each with a seating capacity of 1,000. In the grandiose fashion that had become typical of Alviene’s advertising and annual catalogs, one was dubbed the Temple of the Drama, another the Temple of Musical Comedy, and a third the Temple of Dance. There were now 15 studios, and the faculty had increased to 20. The office entrance switched to 309 W. 23rd St. The new quarters had formerly been the Eighth District Municipal Court, and the stage was placed where the judges’ bench had been (“Alviene School of Stage Arts Enlarging Quarters,” New York Clipper 24 June 1911:5 and “The Alviene School,” New York Dramatic Mirror 21 June 1911:22).

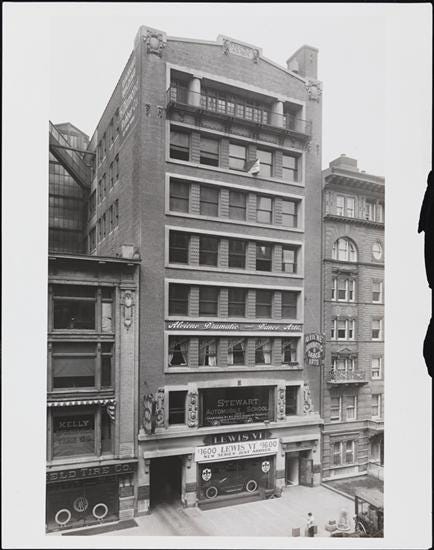

Just four years into the 10-year lease, Alviene had relocated by November 1914 to 225 W. 57th St. in an area that had become a major automobile showroom section of midtown Manhattan. The school was located on the top floors, while the street level housed an auto dealership and the second floor housed the Stewart Automobile School, which offered classes in automobile mechanics[1].

Less than six years later, in 1920 the Alviene Schools moved to 43 W. 72nd St. near the Hotel Majestic on Central Park West, where coincidentally the Astaires had moved after signing with Charles Dillingham in the summer of 1919 (Astaire 71). The school occupied the entire five-story building with a roof garden and little theater on the ground floor (“Alviene Schools Move,” New York Dramatic Mirror 24 July 1920:148), and in some ads started calling itself Alviene University. By 1927, the school moved a dozen blocks farther north to 66 W. 85th St. and changed its name once again to the Alviene Academy of Dramatic and Cultural Arts. By 1945, shortly before Alviene’s death, the school relocated once again to midtown at 1780 Broadway near 58th Street and Columbus Circle.

Alviene garnered various types of publicity over the years, often with releases to the entertainment press or occasional profiles in mainstream news. An article in the New York Sunday Telegraph credited him as the inventor of “The ‘Progressive Ballet’ Society’s Latest Fad” in a story about a four-day sequence of dances offered in elite homes. The article featured a photograph of both “Signor Alvieni” and his wife, La Neva, as well as an elaborate sketch of her leaping in a frilly dress and toe shoes. In 1910, the New York Sun published an extensive profile of Alviene shortly after he had reorganized his school into the Alviene United Stage Training Schools. Characterizing him as a “blond man, who doesn’t show his age,” the article mentions his recently released catalog and describes the published photograph: “a profusion of curls resting on an upraised hand, a white chrysanthemum in his buttonhole, one shirt stud, two ends of an evening dress necktie, cuff buttons, silk lapels and turned over collar…” but contrasts that with his work appearance – mussed hair, “a certain negligence of collar and tie and uncreased trousers” (“All Dramatic Art in One”). In the 1933 catalog, Alviene is again pictured in formal dress, this time with a ribboned pince-nez and the same full head of hair, now turned white. In Astaire’s autobiography, Alviene is remembered as a “kindly, fatherly man with white hair, quite the picturesque dancing master” (Astaire 17).

Through five decades Alviene published advertisements for his schools and their half dozen locations in entertainment periodicals, such as the New York Clipper, the New York Dramatic Mirror, Billboard, the Police Gazette, and Variety, and in specialized dance magazines, such as American Dancer. Alviene also frequently ran classified ads in daily newspapers, such as the New York World, the New York Journal & Advertiser, the New York Morning Telegraph, the New York Evening Telegram, the New York Times, the New York Sun, and the New York Sunday Herald. Later when the golden age of magazines began, Alviene ran advertisements in such diverse publications as Theatre Magazine (starting in 1908), Cosmopolitan, Vanity Fair, Theatre Arts, Harper’s Bazaar, Munsey’s, Everybody’s, Collier’s, House & Garden (1922), and the New Yorker. When movie fan magazines started exploding in the 1910s, Alviene advertised in Motion Picture Story Magazine, Motion Picture magazine, Film Fun, Photoplay, Motion Picture Classic, and Screenland. Frequently the same ad would be run in different publications.

The advertisements had varying focuses over the years. Starting in 1898 and for 20 years thereafter, almost every display ad featured a silhouette that showed him posed with his right arm upstretched and his left pointed down holding a baton, to emphasize his being a ballet master. The silhouette was taken from a photograph that appeared in the National Police Gazette along with a full page of photographs of various students (“Clever Dancers”). The same photograph would later appear in nearly all his school’s catalogs. In 1898 he also started proclaiming his school the largest and the oldest in the world, with ever increasing numbers of graduates (400 in in the 1890s, 1,000 in 1906, 3,000 in 1907, and 4,000 in 1909). Promises of success, both in personal dancing and in professional engagements, were a frequent theme, starting in 1891 when an ad in the New York World claimed “positively no failures” in teaching the waltz (3 November 1891:7). Several years later, an ad described a sworn affidavit by Anthony Debes that “he became a perfect waltzer in four private lessons from Prof. Alviene, of Lenox Conservatory” (New York World 13 February 1898:52). In 1902, he offered $1,000 “to any dancing master in the world who can half way equal my record of successful pupils” (New York Dramatic Mirror 19 July 1902:7). In the entertainment publications, Alviene was offering similar promises: “We guarantee success. Likewise engagements” (New York Clipper 12 March 1898:31) and “All graduate students are assured New York appearances and engagements” (Theatre Magazine, July 1909:vii).

For several years, Alviene’s advertising slogans included variations on that theme, beginning with the lengthy “Success succeeds, originality merits, and honesty always wins” (New York Dramatic Mirror 19 July 1902:7). By the time the Astaires had been working at his school for six months, the slogan became simply “Success Succeeds” (New York Tribune 26 August 1905:Educational Supplement-11). A professional testament of success came from La Noveta (the stage name of Helen B.J. Dunwoodie) in an ad reading “Yes, I was a beginner when I started at Alviene School. After 6 months I went on the stage, signed for 3 years with Mr. Dillingham” (Theatre Magazine, March 1908:xvi), referring to producer Charles Dillingham, who would give the Astaires their first major Broadway success in 1919 with Apple Blossoms.

Speed of instruction was another advertising theme: “The old method required from three to five years to graduate artists. Claude Alviene's new method enables him to accomplish the same results in three to six months, getting his students ready for metropolitan productions. Success guaranteed, failures impossible… Why can't you?" (Theatre Magazine, January 1909:iv). Several years later this evolved into a slogan featured in advertisements that ran in the New York Clipper for more than two years: "Others succeed, why can't you?" During this same period, another common theme was the money to be made: “Earn $35 to $500 weekly.” Ten years later the slogan was “Get on the Stage” with hints of get-rich-quick claims that “the world’s highest kicker and Zita Johann, the youngest leading lady on the stage, were business girls. Stuart, the boy tenor, and Anthony Knilling, now with David Belasco, were transferred from high school to the world-famous ALVIENE THEATRE SCHOOL, one year ago. It’s YOUR opportunity now to enjoy the luxuries of life with other Alviene pupils…” followed by a list of celebrities who had long ago studied with Alviene (New York Times 20 September 1925:19).

Touting the names of famed performers who had at some point studied with Alviene had been a standard feature of his advertisements since 1898 (New York World 13 February 1898:52), when he mentioned stars such as Mazy King, Amy Muller, and Georgia Caine. More than 30 years later, Caine would appear with the Astaires on Broadway, playing their mother in Smiles (1930), their only musical produced by Florenz Ziegfeld. Caine would also have an uncredited role as a charwoman in Astaire’s film The Sky’s the Limit (1943). Over the years, Alviene would list more than 200 different celebrities in his advertisements and catalog, most of whom are no longer well remembered. Nearly a dozen, however, would go on to appear with the Astaires during their vaudeville years, such as Nora Bayes, who appeared with them in 1914, and Joseph Santley, who appeared with them at an Actors Equity Benefit in 1921. Others who appeared with the Astaires on benefit bills in the 1920s included Emma Haig, Gertrude Hoffman, Evelyn Law, Eddie Leonard, Laurette Taylor, and Mary Nash, who would also appear with Astaire in Yolanda and the Thief (1945). In his autobiography, the only fellow student that Astaire mentions is Harry Pilcer, who later married Gaby Deslys (Astaire 17). It’s possible that the Astaires met the young Dolly Sisters (at this point still called Yansci and Roszika Deutsch), who arrived in New York in May 1905 and soon started taking lessons with Alviene at the age of 12 (Chapman 12). Two other celebrities claimed by Alviene with future Astaire connections were Mary Pickford, whom the Astaires met during a summer vacation in 1914 at the Delaware Water Gap where Pickford was filming Fanchon the Cricket, and Justine Johnstone, who starred in the Astaires’ first appearance in a Broadway musical, the revue Over the Top (1917).

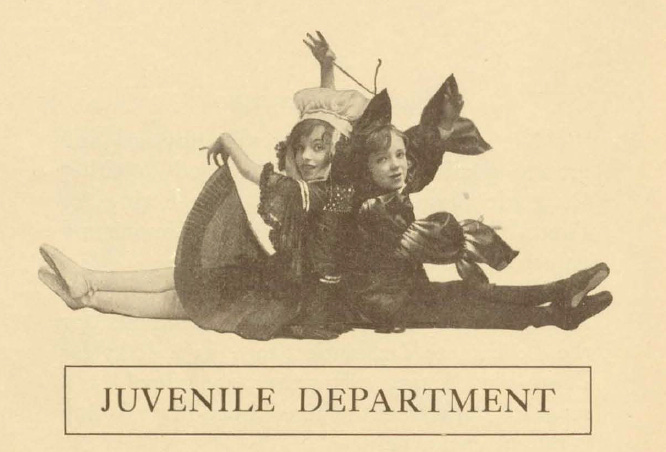

After gaining fame on Broadway in the 1920s, the Astaires became some of the names most frequently listed in the Alviene advertisements. They first appeared, unnamed, in a photograph in the 1915 edition of The Alviene Schools catalog, at the beginning of the Juvenile Department section. The photograph likely came from one of the school’s public recitals that included the Astaires. Two pages later, the Dolly Sisters were shown under the name “Rose and Jean Rodika.” By the 1918 edition of the catalog, the Astaires having signed with the Shuberts and getting positive reviews for Over the Top (1917), the juvenile photograph now included their names, though misspelled “The Astairs.” Their names (still misspelled) started appearing in newspaper advertisements in 1923, claiming Alviene as the “original teacher of Fred and Adele Astair, stars of the Bunch and Judy” (New York Times 7 January 1923:xx). Their names were finally spelled correctly in 1925 (Theatre Magazine, March 1925:68). The 1933 edition of the Alviene catalog, when the school had moved uptown to 66 W. 85th St., now featured an adult photograph of the Astaires from The Band Wagon with the caption “Adele Astaire retired from the stage to become Lady Cavendish. Fred is in Hollywood and Talking Pictures while Broadway awaits him.”

Later in the 1930s, with the memory of the brother and sister team replaced by the Fred and Ginger pairing in a series of hit movies, Alviene’s ads mentioned Fred alone (The American Dancer, October 1935:3), and Fred eventually became the only star mentioned in the ads (New York Times 20 November 1938:170). In some ads Alviene described himself as “the master who personally taught Fred Astaire” (New York Times 3 April 1938:X-8), even though 33 years had passed since Astaire had taken those first dancing classes at the Grand Opera House.

More than just stage celebrities were touted by Alviene. In 1900 an article in the New York World described him as someone “who teaches fashionable women” (4 November 1900:11). In an ad in 1914 he claimed to be “Instructor to the New York 400” (New York Sunday Herald 8 March 1914:II-3) while Vernon and Irene Castle were becoming the darlings of the trendy set. Lists of students who were members of the New York stage and social elite were featured not only in advertisements but also in Alviene’s annual catalogs. The 1933 catalog included a full page of “registrites, social leaders, debutantes, former students or patrons” including Mrs. Gloria Gould, Lady Constance Stewart-Richardson (listed as Lady Constance McKenzie, whose “semi-clad” dancing 20 years earlier on the British and American stage created scandals), Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Mrs. Harry Payne Whitney. Mrs. Whitney’s son “Jock” was a buddy of Fred’s, and she loaned Fred her yacht “Captiva” for cruising up the Hudson River for his honeymoon on July 13, 1933, shortly before he and his bride, Phyllis, flew to Hollywood to begin his movie career.

In the 1920s Alviene would also advertise an illustrious board of directors for the school, including producers William Brady, Henry Miller, and J.J. Shubert, British actor Sir John Martin Harvey, actress Marguerite Clark, and critic Alan Dale (New York Times 30 August 1925:14). Earlier Alviene had run advertisements claiming to be “endorsed by the celebrated dramatic critic Alan Dale” and listing “Mr. Alan Dale’s beautiful daughter Miss Daisy Dale” as a student (New York Dramatic Mirror 6 October 1906:23). Alviene would sum it up with another grandiose slogan: “The stupendous success of pupil-celebrities astonishes the profession” (New York Times 25 February 1923:17).

Over the years, Alviene’s ads and the school’s offerings followed trends in show business, technology, and dance styles. After initially focusing on waltzes and private lessons, by 1898 he was advertising “stage dancing” and added singing and dancing classes as well as complete specialties, with “songs, sketches and monologues free to pupils” and promised “engagements secured when pupils are competent” (New York Clipper 12 March 1898:31). As vaudeville expanded in the early 1900s, Alviene not only advertised more steadily in publications devoted to that branch of entertainment but also began including it as one of the school’s focuses, putting it on an equal footing with his dramatic and dancing areas (New York Clipper 21 April 1906:266) and even labeling his institute Alviene's Vaudeville School of Acting alongside his Institute of Stage Dancing (Variety 1 December 1906:14). As theatrical styles began to change before World War I, musical comedy was added to the program of study (Theatre Magazine, January 1911:viii), and when movies began drawing big crowds and pioneering studios in New York began churning out films, Alviene added film acting to his curricula as early as 1913 in advertisements in Motion Picture Story magazine (October 1913:171), though the classes were called “photo-play acting” in his 1915 catalog. By 1933, radio classes joined the offerings in his catalog.

Seeking to expand his reach beyond New York, Alviene was offering to teach dancing by mail (New York Dramatic Mirror 30 November 1901:27), and a decade later as Victrola ownership became more common, he added “Personal instruction by phonograph at your home if you cannot come on to New York" (New York Clipper 29 April 1911:24).

Never one to focus on a single motive for potential students, Alviene also stressed over the years the physical and psychological benefits of dancing. In a column published in the Oswego Daily Palladium on October 6, 1891, “Claude M. Alviene, physical instructor,” argued that lack of proper exercise for businessmen and women led to mental and physical deterioration. He advocated that schools add regular exercise for children as well, but since adults were similarly spending most of their workdays behind desks, exercise was just as important for them. A few years later, Alviene was mentioned in an article in New York World suggesting dancing as a cure for “nervous prostration” and believing that a twitching hand could be cured by dancing with castanets (“The New Cure”). Twenty-five years later, he would run a classified ad proclaiming “Reduce by Dancing: Enjoy slenderness, poise and health. Men, women, children; ages seven to seventy” (New York Times 1 December 1925:52).

The ever-changing styles of dance, both personal and professional, can be traced through Alviene’s ads over the years. Starting with the waltz in 1891, he would mention dozens of dances including clogs, reels and jigs. International styles ranged from French cognette and Spanish to Grecian, Russian and Argentine tangos. Eccentric dancing, cycle, fire, grotesque and serpentine were offered in the ever-expanding search for novelty. In the early 1910s, a dance craze began, spearheaded by Vernon and Irene Castle, who had their own dance studio, Castle House, at 26 E. 46th St. at Madison Avenue. In response Alviene added the Maxixe and the Fox Trot to his repertoire and continued to advertise his school but now alongside dozens of competitors that had sprung up throughout Manhattan (New York Sunday Herald 8 March 1914:II-3).

In 1911 as the dance craze was beginning, Alviene was quoted extensively in an article about New York’s fad for the Grizzly Bear. “I do not think the dance particularly pretty or graceful. But, like the Boston and other recent favorites, it lends itself to freedom of movement and a certain romping tendency common among young people. However, when it is properly danced, there is nothing offensive to modesty.” In the “improper” manner “the man extends his arms straightforward, resting each hand under the girl’s arms. The girl puts her arms directly around the shoulders of the man, and they are as close together as they can be and move” (“New Yorkers Hug Grizzly Bear”).

Alviene had similarly been concerned about the vulgarity of an earlier dance craze, the Salomé. In an article in the magazine section of the New York World (“What Will They Do Next?”), Alviene condemned the shocking costumes and grotesque contortions of the Salomé dance, which had become a raging success on New York’s vaudeville stages. One of its most famous performers had been one of his former pupils, Gertrude Hoffman, whose performance of “A Vision of Salomé” at Hammerstein’s Victoria Garden in July 1908 set attendance records and helped create “Salomania.” Despite his criticism, within less than a year Alviene was advertising instruction in the Salomé dance (New York Clipper 20 February 1909:28G).

As the dance craze of the 1910s expanded, Alviene grasped the opportunity to expand his reputation nationally. In 1913, he penned an article on how to dance the one-step, accompanied by eight different sketches of a couple in evening dress going through the dance’s varied phases (Alviene, "How to Dance the One Step"). The article in the San Francisco Call labeled Alviene the “dancing master of the Colony Club,” New York’s exclusive social club for women founded 10 years earlier including Vanderbilts and Whitneys among its original members. Four years later, Alviene attempted to capitalize on the patriotic Uncle Sam spirit sweeping the nation after the country’s entry into World War I by inventing a military waltz he called “The Sammy.” Detailed instructions with photos and steps were again published in a variety of newspapers in October 1917 (Marbourg).

In addition to dancing, acting, and singing instruction, Alviene expanded his business to a wide range of performance choreography and the creation and selling of dance routines. Among his choreographic assignments was the staging of Harvard’s Hasty Pudding Shows and Princeton’s Triangle Club Shows. Hired in 1903, Alviene was the Triangle Club’s first professional choreographer and is credited with originating the all-male kick line for the show Tabasco Land (1905-1906), which became a longstanding tradition for Triangle shows (Serraro). Among the productions he staged was The Pursuit of Priscilla (1913-1914), but he appears to have stopped working for the Triangle Club by the time F. Scott Fitzgerald matriculated at Princeton and wrote lyrics for the club’s elaborate productions (1915-1917). Also in 1905, Alviene was credited with posing the flower maidens in the playbill of the New National Theatre’s production of Wagner’s Parsifal on January 16, 1905, in Washington, D.C.

Alviene’s design of dances and ensembles was not always so high-toned. In 1899, he had designed what was described as a “living cake walk dance” for Mlle. Senga (New York Dramatic Mirror 15 July 1899:23), which involved her stepping on the shoulders of four men. Three months later he was announcing in the same periodical that Senga was no longer connected with the living cake walk (“Matters of Fact”), but a photograph that appeared six months later in The National Police Gazette (7 April 1900:4) shows both Senga and Billy Van’s Komedy Koon Quartette with a caption noting that the dance, which had created a sensation, was patented and copyrighted by Alviene. Two weeks later, Senga was headed to London to perform the Living Cake Walk (“Vaudeville Jottings,”21 April 1900).

Props became important features of his dance routines, as would be the case for the act he designed for the Astaires. In 1895 he copyrighted a routine dubbed “The Fire Star Electric Dance” (New York Dramatic Mirror 19 October 1895:17). In 1900 he developed a new dance using four horses and a racing boat (“Artistic Comediennes”). In 1915, Alviene announced he had created a special dance number to be used in a film featuring Mary Fuller and a snake borrowed from the Bronx Zoo (“Notes”). Surely among the most bizarre was one he created for La Neva, who was described as an “electrical scenic dancer” (Elmira, NY, Dixie’s Theatre). The dance number was called “The Champagne Promenade,” as she danced atop champagne bottles arranged on stairs while carrying a child in her arms. She performed the act at various vaudeville theaters in New York City, including Koster & Bial’s in late February 1901, where on the opening night the Gerry Society ordered her to discontinue carrying the child. The next night she carried a large doll, so realistic that a Gerry agent stormed backstage after the performance to demand why his order had been disregarded (“Miss Clipper’s Anecdotes”). She appeared at the Brooklyn Orpheum in another Alviene designed dance called “The Vision of the Moon” (it had earlier been called “The Maid in the Moon”), and when she took the act on tour to Detroit in 1902 another routine was added where she danced atop the bayonets of guns, which discharged as she stepped on them (“Vaudeville and Minstrel”). After a successful week at the Orpheum in Brooklyn, Alviene had several entertainment weeklies publish that he had presented her with a large diamond marquise ring modeled after her ballet slipper (“Vaudeville Jottings,”16 March 1901). Neva would later marry Alviene and become his partner in the schools, which she continued to operate after this death in 1946. In his autobiography, Astaire mentions her and recalls that he and his sister liked La Neva and that she had been a well-known toe dancer (Astaire 17).

SOURCES

"All Dramatic Art in One: Alviene Schools Ready to Teach Almost Any One." The (New York) Sun 12 June 1910: 9.

Alviene, Claude. “How to Dance the One Step"." San Francisco Sunday Call 2 March 1913: 4.

“Artistic Comediennes, Clever Comedians,” The National Police Gazette 12 May 1900:2

Astaire, Fred. Steps in Time. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1959.

Chapman, Gary. The Delectable Dollies: The Dolly Sisters, Icons of the Jazz Age. Phoenix Mill: Sutton Publishing, 2006.

“Clever Dancers” Who Have Gained Fame,” National Police Gazette 10 March 1900:4.

Elmira, NY, Dixie’s Theatre, New York Clipper 22 December 1900:954.

Marbourg, Nina C. ""How to Dance the 'Sammy': Professor Claude Alviene's New Military Novelty and Just How Its Jolly Steps Are Performed"." The Sunday Oregonian 7 October 1917: 4.

“Matters of Fact,” New York Dramatic Mirror 14 October 1899:9.

“Miss Clipper’s Anecdotes,” New York Clipper 2 March 1901:2.

“The New Cure for Nervous Prostration—Learn to Dance,” New York World 4 November 1900:11).

"New Yorkers Hug Grizzly Bear." Elmira (NY) Morning Telegram 17 December 1911.

“Notes,” New York Clipper 8 May 1915:19.

Parsifal Theater Program. Washington, D.C.: New National Theatre, 1905. [https://lccn.loc.gov/2012658991].

Schweitzer, Marlis. "The Salome Epidemic: Degeneracy, Disease, and Race Suicide." The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Theater. Ed. Nadine George-Graves. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015. 890-921.

Serraro, Jessica. A Lotta Kicks: 125 Years of the Triangle Club. 18 November 2016. 18 February 2019. <https://blogs.princeton.edu/mudd/2016/11/a-lotta-kicks/>.

“Vaudeville and Minstrel,” New York Clipper 28 June 1902:394.

“Vaudeville Jottings,” New York Dramatic Mirror 16 March 1901:21.

“Vaudeville Jottings,” New York Dramatic Mirror 21 April 1900:18.

“What Will They Do Next? And Call It Dancing!” New York World 16 August 1908:Magazine 7.

[1]The auto dealership sold the Lewis “VI” cars for the LPC Motor Car Co., which was based in Racine, Wisc. http://www.american-automobiles.com/Lewis.html