1.21 - Boffo Intro for Show Biz Pub

Variety Publishes First Issue in December 1905

In November 1905 there were three weekly entertainment trade papers that regularly listed vaudeville routes – the New York Clipper, Billboard and the New York Dramatic Mirror – but in December they would be joined by a rival paper, which would outlast them all: Variety.

Founded by Sime Silverman, a native of Syracuse who worked as a bookkeeper for his father’s loan business but whose passion was vaudeville, Variety debuted on December 16. The previous year (1904) Silverman had been fired as a part-time reviewer for the New York Morning Telegraph because he had written a critical review of the jugglers Redford & Winchester, who had run a Christmas ad in the paper (Besas 27). The Astaires would appear on vaudeville bills with Vincent Redford and Gene Winchester twice in 1914.

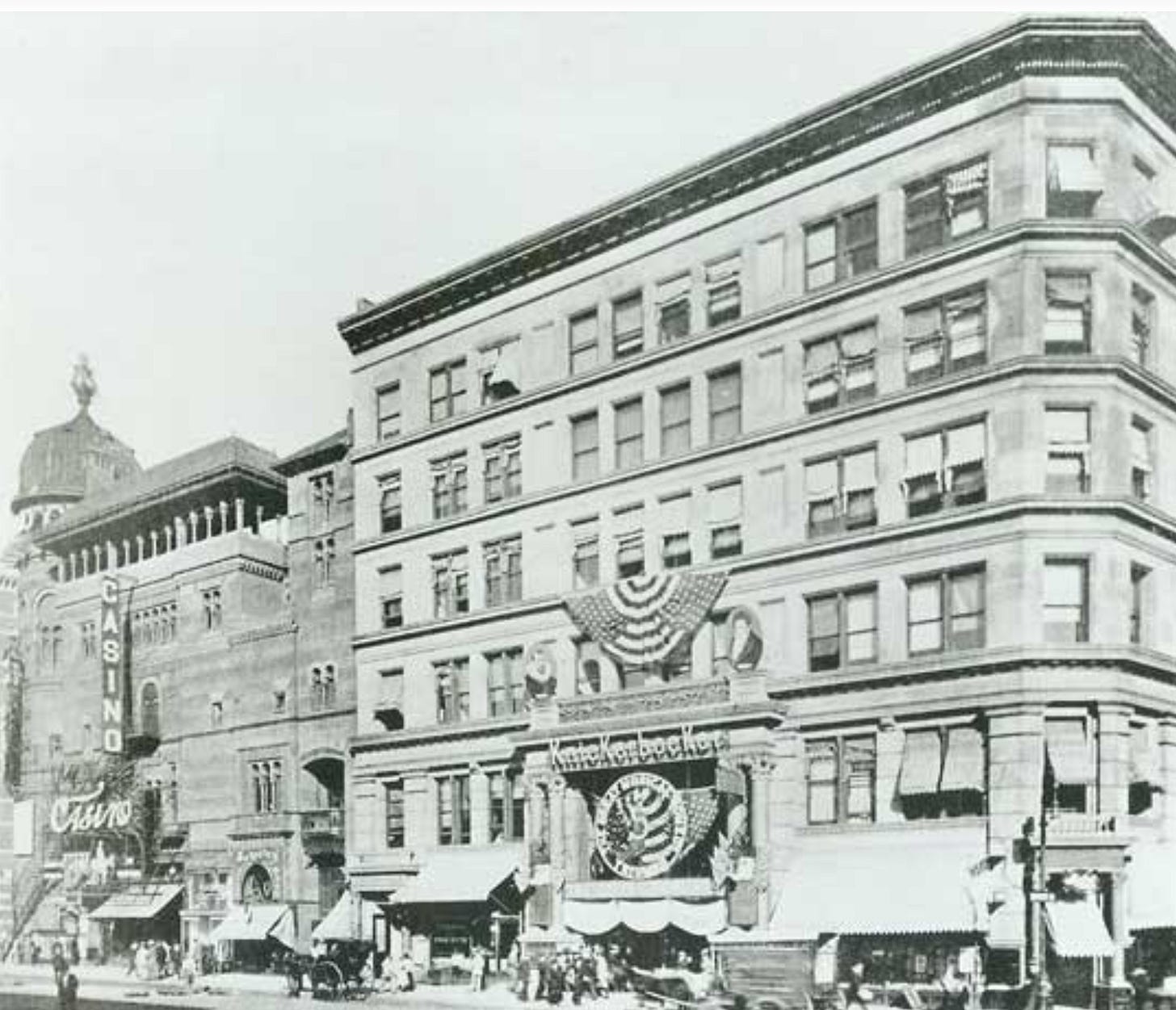

Silverman leased office space in the Knickerbocker Building above the Knickerbocker Theater at 1402 Broadway, on the east side of Broadway between 38th and 39th streets, next door to the Casino Theatre and a block south of the Metropolitan Opera House at 1411 Broadway. Across the hall were the offices of Charles Dillingham (Besas 31), for whom the Astaires would receive their first headlining roles.

A year after being fired for writing an honest review not shaped by the act's advertising, Silverman stated his guiding philosophy in Variety's debut issue: "The first, foremost and extraordinary feature of it will be FAIRNESS. Whatever there is to be printed of interest to the professional world WILL BE PRINTED WITHOUT REGARD TO WHOSE NAME IS MENTIONED OR THE ADVERTISING COLUMNS. The reviews will be written conscientiously, and the truth only told. If it hurts it is at least said in fairness and impartiality."

The first issue, published on a Saturday, sold for 5¢ and featured only 16 pages, with a meager two pages of ads, mostly from agents, sketch writers and song publishers. The competing entertainment weeklies were also published on Saturdays and sold for 10¢. The New York Clipper, with offices at 47 W. 28th St., had 28 pages. Billboard, published in Cincinnati but with Manhattan offices in the Holland Building at 1440 Broadway, featured 40 pages. The New YorkDramatic Mirror, with offices at 121 W. 42nd St. between Broadway and Sixth Avenue, had 24 pages. Ironically Silverman's first ads for Variety ran in the Morning Telegraph on December 3 and 10. He also ran ads in the Clipper, Billboard and the Dramatic Mirror on December 16, all touting Variety as "The Vaudeville Paper."

The Astaires would place their first significant advertisement in Variety on July 14 of the following year, and it would also be the first entertainment weekly to run their photograph in a cover inset photo on March 30, 1907. Variety would be the earliest of the trade papers to publish reviews of the Astaires, starting with a short "correspondence" notice on March 10, 1906, as they began their first vaudeville routes, and eventually a longer review in 1908 in the "New Acts of the Week" column (Freeman 12), a novel feature in Variety that began with its premier issue, where one of the reviewers offered detailed critiques of vaudeville acts presented for the first time in New York with "sufficient spaced allowed for a thorough digest" (New Acts).

Among the half dozen new acts reviewed in the Variety's first issue was one vaudeville team who would later perform on a bill with the Astaires: Frederick Hallen and Mollie Fuller would appear with the Astaires in 1915 (August 3 through September 4) at the New Brighton theater in Brighton Beach and in 1916 (March 20-25) in Boston (Keith's). Ten other acts who would eventually share stages with the Astaires were reviewed in that first issue of Variety. These included Mike Bernard (who would appear on a Shubert Sunday Concert on Nov. 11, 1917), Lew Hawkins (vaudeville bills in 1914), the Heras Family acrobats (vaudeville October 1916), Mayme Remington (Wilmington, Delaware, in 1908), Hyams & McIntyre (Harrisburg, April 1914), Cartmel & Harris, and the Dixie Serenaders (Philadelphia, August 1907). Today the best known of the acts named in that first issue of Variety with an Astaire association was Will Rogers, who would appear with the Astaires at benefit concerts in 1925 and 1933. Harry Pilcer, whom the Astaires had met at Claude Alviene's school earlier in the year, was also reviewed in Variety’s premiere issue.

Silverman demonstrated his philosophy of keeping Variety's columns clean of "wash notices" (i.e. whitewash reviews) in the first issue. In his review of Emma Carus at Proctor's 23rd Street, he opined that "She is growing careless of her voice, but does not strike the deep contralto as often as formerly. Two of her [five] selections were good; the others indifferent" (Proctor's Twenty-Third St.). In contrast, the New York Clipper's anonymous reviewer described Carus as being "in excellent voice, made one of the biggest success of the bill…." (Proctor's Twenty-third Street Theatre). The Astaires would appear on vaudeville bills with Carus a decade later: at the Colonial in Manhattan the week of December 17, 1915, and in Detroit at the Temple Theatre the week of June 20, 1917. They would also appear with Carus at a Shubert Sunday Concert at the Winter Garden Theatre on November 3, 1918.

The controversy surrounding Sunday concerts would be one of the first topics covered in the news columns of that first issue of Variety. The New York Supreme Court had recently reversed a lower court decision and found that performing artists could not recover payments for Sunday performances, since such performances violated the state's Sunday closing laws and therefore constituted an illegal contract. Silverman suggested a way of protecting both artist and manager by having contracts establish a full agreed price for a six-day week with an added memorandum where the artist agreed to perform without charge on specific Sundays "in such manner as the manager may direct" (Notes).

Later in the same column, Silverman blasted producer F.F. Proctor for using the Sunday closing laws to the detriment of performers. At the time, Proctor's theaters in New York City were holding Sunday performances, which were not permitted in his upstate houses. Artists who had been booked for the week in Proctor's theaters in Albany and Troy were notified that they would be expected to perform on Sunday in the New York City theaters on the Sunday following their closing upstate. The artists objected not only to the requirement not being specified in their contracts but also to Proctor paying only one transportation fare for each act. Silverman argued that "were the artists in this country properly organized" then steps could have been taken to make formal protests in what were described as "indignation meetings" (Silverman, “Proctor’s Extraordinary Demand”). Variety would find itself tackling conflicts between artists and managers many times over the next 15 years, as actors began to organize through the White Rats and eventually the Actors Equity Association, and as producers fought back with threats of cancelling acts through their circuits and establishing blacklists.

The Astaires would find themselves entangled in such conflicts multiple times during their vaudeville and early Broadway careers. Once they signed contracts with the Shuberts in 1917, they would also be required to perform in numerous Sunday concerts. But the first issue they would face as they began their vaudeville careers would involve their age and laws that barred young performers from the stages of New York City. Variety first broached this topic in its second issue (December 23) in a thinly veiled satire on the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, whose chief counsel Elbridge T. Gerry led a crusade to stop those under the age of 16 from performing in the city's theaters. Silverman proposed creating the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to the Gallery Gods (SPCGG) to address the unfair usage of "the poor little youngster who plunks down his ten cents at the box office window, climbs seven flights of stairs and then is compelled“ to listen to soubrettes singing over and over the chorus of a song from a music publisher who has bribed her with a diamond ring. Using a snickering manner that would become the standard Variety style, Silverman described singers who insisted that the audience join in the songs until "the small boy comes down from the gallery at the end of the show with a sore throat…. The youth of America is entitled to protection. They should not be coerced into singing a song just because the publisher is generous to the singer" (Silverman, S.P.C.G.G.).

As their first year in New York drew to a close, Fred and Adele were still filled with excitement from the grand adventure they had begun in January. They had settled into life in the teeming metropolis along the vast diversity of 23rd Street. They looked up at the skyscrapers rising ever higher in Manhattan and marveled at famed sights such as Coney Island, Central Park and the city’s mammoth department stores, museums, and theaters. When their father, Fritz, had traveled east from Omaha from time to time from Omaha, they were treated to special dining excursions, but the tight bond with their mother, Anna, was formed in the routines of boarding house tutoring, dance school lessons, and family fellowship. Their initial purpose in coming to New York was being realized, as they practiced dancing with two masters at the Grand and Metropolitan opera houses. They had rehearsed again and again a cute vaudeville turn created for them by Claude Alviene and taken it on the road several times. And in a city whose first impression for them had been busy speed, they had moved about via elevated trains, subways, river ferries, and railroad cars to upstate New York and the Jersey Shore. The audacious plan might be working. Most notably they now sported a strange new name, abandoning the awkward, Germanic sounds of “Austerlitz” for a unique, cosmopolitan calling card “Astaire” that hinted at their first steps up the stairs to stardom.

SOURCES

Besas, Peter. Inside Variety: The Story of the Bible of Show Business (1905-1987). New York: Ars Millenii, 2000.

Freeman, Charlie (Dash). "New Acts of the Week: The Astaires." Variety 17 October 1908: 12.

"New Acts." Variety 16 December 1905: 11.

Notes. Variety 16 December 1905: 3.

"Proctor's Twenty-Third St." Variety 16 December 1905: 9.

"Proctor's Twenty-third Street Theatre." New York Clipper 16 December 1905: 1104.

Silverman, Sime. “Proctor’s Extraordinary Demand.” Variety 16 December 1905:3.

—. "S.P.C.G.G." Variety 23 December 1905: 14.